CKB-Virtual Machine (CKB-VM) is a RISC-V instruction set based VM for executing smart contracts on Nervos CKB, written in Rust.

Introduction

We considered the features that the CKB-VM will require during virtual machine (VM) selection for our layer 1 blockchain (Nervos CKB).

For a VM to be used on a blockchain, it must meet the following conditions:

- Certainty: For a fixed program and input, the VM must always return the same output result. The result must not be dependant on external conditions such as time or the running environment.

- Security: The VM must not affect the operation of its host.

Above we have listed mandatory conditions, though we have considered the design of a VM that will best serve the CKB’s objectives. After our research, we propose the following features :

- Flexibility: It is our goal to design a VM flexible enough to run for years or decades, allowing the CKB to evolve along with the field of cryptography. Current cryptographic primitives such as secp256k1 may no longer be used and valuable new primitives and techniques (such as Schnorr or post-quantum signatures) will continue to emerge. New innovations should be made available to programs running on the VM and primitives that are no longer used should be able to be disregarded. To demonstrate our requirement, we can examine Bitcoin. Currently Bitcoin makes use of SIGHASH for transaction signing and for consensus utilizes the SHA-256 hash algorithm. Can we say with certainty that SIGHASH will be best after several years or that SHA-256 will be suitable as a stable hash algorithm as computing capabilities increase over time? Currently a hard fork is required to implement new cryptographic primitives in all blockchain protocols we have examined. In designing the CKB, we explored the possibility of reducing this hard fork requirement through the design of the VM layer. The question we ask is, can we allow the update of cryptographic algorithms or addition of new transaction verification logic to the VM? While secp256k1 is still used, would the implementation of signature verification become more efficient if driven by economic incentives? If someone finds out a better way to implement algorithms used on CKB or just need a new cryptographic primitive, can we enable he/she to do so freely? We hope the VM layer of the CKB will provide maximum flexibility and broad implementation support to enable the exploration of these type of questions. With the CKB-VM’s design, users will not need to wait for implementation of a hard fork to utilize new cryptographic innovations.

- Runtime Visibility: After conducting research on the VM of existing blockchains, we have observed a problem. We will illustrate using Bitcoin as an example again: the VM layer of Bitcoin only provides one stack (and this VM does not know the amount of data that can be stored on the stack, or the stack depth). VMs implemented in stack mode also exhibit this issue. Though the consensus layer may provide the stack depth definition or indirectly provide the stack depth (based on the code length or gas restriction), programs running on the VM cannot obtain the stack depth. Because developers of programs running on the VM must guess the program running status, programs running on the VM cannot use all potential capabilities of the VM. Based on this thought, we have considered preferentially defining the restrictions of all resources during VM operation, including the gas restrictions and stack space size, and providing programs running on the VM the ability to query resource usage. This will allow programs running on the VM to utilize different algorithms based on resource availability. With this design, programs can utilize the VM’s full potential. With this construction, we see more VM flexibility enabled in the following scenarios: a) Different policies can be selected for contracts that store data, based on cell capacity. When there is sufficient cell capacity, a program can directly store data to reduce the number of CPU cycles used, or when cell capacity is constrained, the program can compress data to fit the smaller capacity, simply by utilizing more CPU cycles. b) Different handling mechanisms can be selected for contracts according to the amount of cell data and size of remaining memory. When there is a small amount of cell data or substantial remaining memory, all cell data can be read to memory for handling. When there is a large amount of cell data or little remaining memory, a portion of memory can be read for each operation, an operation similar to swap memory. c) For some common contracts, hash algorithms for example, different handling methods can be selected based on the number of CPU cycles provided by the user. For example, SHA3–256 is secure enough to meet most requirements, however, a contract may utilize the SHA3–512 algorithm to meet different security requirements by using more CPU cycles.

- Runtime overhead: The gas mechanism in the Ethereum virtual machine (EVM) is a brilliant design. It solves the halting problem in the context of a blockchain VM, and allows for turing-complete computation on a fully decentralized virtual machine. However, we have observed that it is difficult to design a proper gas computation method for different EVM opcodes. We have found that the EVM has adjusted the gas computation mechanism in almost every version update. We wonder: can we ensure more efficient overhead calculation through VM design?

We have considered the design of a VM that can deliver all of these features and have found that there is not an existing solution that can achieve our vision of the CKB.

Inspiration

We can design a VM that has advanced language features. For example: a VM for static verification or a VM that supports advanced data structures or various cryptographic algorithms. However, all blockchain projects must run under a Von Neumann CPU architecture (x86, x86_64, ARM) and all advanced VM features must be mapped to assembly instructions on current generation of CPU architecture, there is no way around this restriction.

For example, V8 might maintain the illusion that an infinite amount of memory is available, but deep down in V8, a sophisticated garbage collection algorithm must be implemented to support this behavior on a limited amount of linear memory space. Similarly, Haskell or Idris might have advanced static type checking that can prove (in a way) that software works correctly, but after type checking is done, there will still be a layer to translate type checked operations to unchecked raw x86_64 assembly instructions.

The main takeaway here is that we cannot deviate much from current system architectures. In other words, any VM will be implemented via plain assembly instructions at the very bottom of the software stack.

An obvious point comes to mind: Why not use a real CPU instruction set that complies with the current system architecture for our VM?

In this way, we will not lose any possibility for adding static verification, advanced data structures or cryptographic algorithms and we can maximize VM flexibility regardless of the data structures or algorithms that we provide in the VM. In addition, with a real CPU instruction set, we can really enable developers to develop any contracts that suit their needs, providing the maximum level of flexibility with the CKB.

It might appear that a higher level VM would make implementing certain things easier, but we believe this is not the case: any higher level VM, no matter how flexible, will inevitably introduce certain semantic constraints in its design. As a consequence, a higher level VM might embrace a variety of languages with different syntaxes, but these languages almost always share the same semantics underneath for performance reasons. The flexibility of a VM will be limited this way, which is not something we want to see in CKB.

Additionally, a higher level VM will most likely include higher level data structures and algorithms. We understand that as CKB developers, we can never imagine all of the different possible ways people might use the CKB. So any higher level data structures and algorithms we build may be suitable for one set of applications, but not for other applications. These embedded data structures or algorithms might slowly become a burden, serving no purpose beyond compatibility.

In addition to flexibility, a VM with real CPU instruction set will provide additional benefits:

- Stability: In contrast to instruction sets designed for VM implemented as software, CPU instruction sets designed for hardware are hard to modify once finalized and used in chips, which makes for a very stable base compared to software VM instruction sets. This property coincides with the requirement of a layer 1 blockchain VM, because a stable instruction set will mean less hard forks, without sacrificing flexibility.

- Runtime visibility: A physical CPU only requires registers and a memory block to run and space in memory is conventionally specified as it is used in the stack during operation. By specifying the memory space size during VM operation, we can obtain the stack space usage during program execution based on the stack pointer within the VM, maximizing visibility of runtime status. CKB VM programs can adjust the stack pointer, change area allocation in memory and even enlarge or shrink the stack area size as needed, providing increased VM flexibility. Current CPU instruction sets also provide a count of elapsed cycles, allowing a running overhead status query for the VM.

- Runtime overhead: For a VM with real CPU instruction set, runtime overhead is easily managed. When a CPU is provided, the number of cycles required for each instruction execution (without considering the pipeline) is fixed. We can use a real CPU as the implementation base for the VM of the CKB. We can design the overhead requirements for the CKB VM based on the number of cycles required for running each instruction on a real CPU. Data obtained in this way will accurately reflect the required overhead of new algorithms when they are implemented.

Utilization of a real CPU instruction set has one key disadvantage when compared to VMs that implement cryptographic algorithms through opcodes or native VM instruction sets: performance.

However, according to our research and test results, we can optimize the cryptographic algorithms running on a VM based on real CPU instruction set to meet CKB application needs through proper optimization and just-in-time (JIT) compiler implementation. In approaching JIT, our starting point is an underlying instruction set, not an advanced language such as JavaScript, yielding a lower workload and better performance.

After the decision has been made to go with a real CPU instruction set, the next step is to choose which set to use. Commonly used instruction sets include x86 or ARM instruction sets. According to our evaluation, we consider RISC-V instruction set to be the best choice for the CKB VM.

RISC-V

RISC-V is an open-source RISC instruction set architecture (ISA) designed by professors of the University of California, Berkeley in 2010. The aim of RISC-V is to provide a common CPU ISA that enables the next generation of system architecture development for several decades without the burden of legacy architecture issues.

RISC-V can meet implementation requirements ranging from small-sized microprocessors with low power consumption to high-performance data center (DC) processors in all scenarios. Compared with other CPU instruction sets, the RISC-V instruction set has the following advantages:

- Openness: Both the core design and implementation of RISC-V are provided under a BSD license. All companies and agencies can utilize the RISC-V instruction set and create new hardware/software without restriction.

- Simplicity: As a RISC instruction set, the 32-bit integer core instruction set of RISC-V has only 41 instructions. Adding support for 64-bit integers, the instruction set only has about 50 instructions. An x86 instruction set may have thousands of instructions, compared to this, the RISC-V instruction set is easily implemented and prevents bugs while providing the same functionality.

- Modular mechanism: With a simplified core, RISC-V also provides a modular mechanism to provide more extended instruction sets. For example, the CKB might choose to implement the V extension defined in the RISC-V core to support vector computing or add extended instruction sets for 256-bit integer computing, providing the possibility of high-performance cryptographic algorithms.

- Wide support: The RISC-V instruction set is supported by compilers such as GCC and LLVM. Rust and Go language implementations based on RISC-V are being developed. The VM implementation of CKB will use the widely implemented ELF format, CKB VM contracts can be developed using any language that can be compiled to RISC-V instructions.

- Maturity: The RISC-V core instruction set has been finalized and frozen, all RISC-V implementations in the future need to be backward compatible. This removes the possibility of a CKB hard fork resulting from a VM instruction update. Additionally, the RISC-V instruction set has hardware implementations and has been verified in real-world application scenarios. RISC-V does not have the potential risks that may exist in other less-supported instruction sets.

Even though other instruction sets may have some of the qualities listed above, the RISC-V instruction set is the only one that delivers all of them according to our evaluation. Based on this, we have chosen to implement CKB VM with the RISC-V instruction set and utilize the ELF format for smart contracts to ensure wide language support.

In addition, we will add dynamic linking for CKB VM to ensure cell sharing. Even though the official CKB implementation will provide popular cryptographic primitives, we encourage the community to provide more optimized cryptographic algorithm implementations to reduce runtime overhead (CPU cycles).

The topic of developer incentives to improve cryptographic primitives on CKB is interesting and has been frequently discussed among the CKB team. It is our hope that the CKB VM will develop and improve with the evolution of cryptography and community, without the need for hard forks to upgrade the protocol.

Example Contract

The following example shows a minimal contract that can run on the CKB VM:

int main()

{

return 0;

}

The following command can be used to compile the code with GCC:

riscv64-unknown-elf-gcc main.c -o main

A CKB contract is a binary file that complies with traditional Unix invocation methods. Input parameters can be provided through argc/argv, and the output result is presented by the return value of the main function.

A value of 0 indicates that contract invocation was successful, other values indicate contract invocation failure.

To simplify the example, we have implemented the contract above in C. However, any language that can be compiled to the RISC-V instruction set can be used for CKB contract development.

- The RISC-V instruction set for the Rust language is being developed, with support for the RISC-V 32-bit instruction set being incorporated nightly. 64-bit instruction set support in LLVM is under development.

- The RISC-V instruction set for the Go language is also being developed.

- For higher level languages, we can directly compile their C implementations to RISC-V binaries and leverage “VM on top of VM” techniques to enable contracts written in these languages on CKB. For example, mruby can be compiled into RISC-V binaries to enable Ruby based contract development. This method can be utilized with the micropython-based Python language and the duktape-based JavaScript language as well. Even contracts compiled to EVM bytecode or Bitcoin Script can be compiled to CKB VM bytecode. These contracts may have heavier running overhead (CPU cycles) than contracts implemented using lower level languages. The development time saved here and security benefits might be more valuable than incurring cycle costs in some scenarios, though we see clear advantages in legacy contract migration to more efficient bytecode.

Outside of the simplest contracts, the CKB also provides a system library to meet the following requirements:

- Support the libc core library

- Support dynamic linking to reduce the space occupied by the current contract. For example, a library can be provided by loading a system cell in to the VM via dynamic link.

- Read transaction content, the CKB VM will have Bitcoin’s SIGHASH-like functions within the VM to maximize contract flexibility.

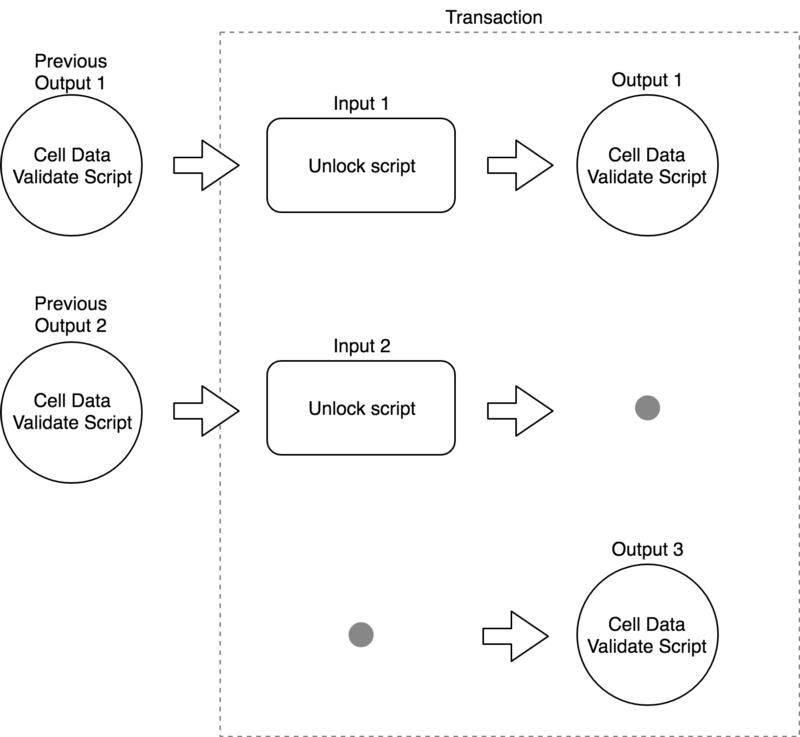

The following figure shows the CKB contract verification model based on a preceding system library:

As shown in the preceding figure, a CKB transaction consists of inputs and outputs. While the transaction may also contain Deps (dependencies that contain data or code needed when running a contract), these only affect contract implementation and are omitted from the transaction model.

Each input to the transaction references an existing cell. A transaction can overwrite, destroy or generate a cell. Consensus rules enforce that the capacity of all output cells in the transaction cannot exceed the capacity of all input cells.

The CKB VM uses the following criteria to verify contracts:

- Each input contains an unlock script, allowing for validation that the transaction originator can utilize the cell referenced by that input. The CKB uses the VM to run the unlock script for verification. The unlock script will usually specify the signature algorithm (for example: SIGHASH-ALL-SHA3-SECP256K) and contain the signature generated by the transaction originator. A CKB contract can use an API to read transaction content to implement SIGHASH-related computing, providing maximum flexibility.

- Each cell may contain a validation script to check whether the cell data meets the previously specified conditions. For example, we can create a cell to save user-defined tokens. After the cell is created, we verify the number of tokens in input cells is greater than or equal to the number of tokens in the output cells to ensure that no additional tokens have been created in the transaction. To enhance security, CKB contract developers can also leverage special contracts to ensure the validation scripts of a cell cannot be modified after the cell has been created.

Input Cell Validation Example

Based on the above description of the CKB VM security model, we will first implement a complete SIGHASH-ALL-SHA3-SECP256K1 contract to verify the provided signature and prove the transaction originator has the ability to consume the current cell.

// For simplicity, we are keeping pubkey in the contract, however this

// solution has a potential problem: even though many contracts might share

// the very same structure, keeping pubkey here will make each contract

// quite different, preventing common contract sharing. In CKB we will

// provide ways to share common contract while still enabling each user

// to embed their own pubkey.

char* PUBKEY = "this is a pubkey";

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

// We need 2 arguments for this contract

// * The first argument is contract name, this is for compatibility issue

// * The second argument is signature for current contract input

if (argc < 2) {

return -1;

}

// This function loads current transaction into VM memory, and returns the

// pointer to serialized transaction data. Notice ckb_mmap might preprocess

// the transaction a bit, such as removing signatures in all tx inputs to

// avoid chicken-egg problem when signing signature.

int length = 0;

char* tx = ckb_mmap(CKB_TX, &length);

if (tx == NULL) {

return -2;

}

// This function dynamically links sha3 library to current VM memory space

void *sha3_handle = ckb_dlopen("sha3");

void (*sha3_func)(const char*, int, char*) = ckb_dlsym("sha3_256");

// Here we run sha3 on all the transaction data, simulating a SIGHASH_ALL process,

// a different contract might choose to deserialize and only hash certain part

// of the transaction

char hash[32];

sha3_func(tx, length, hash);

// Now we load secp256k1 module.

void *secp_handle = ckb_dlopen("secp256k1");

int (*secp_verify_func)(const char*, int, const char*, int, const char*, int) =

ckb_dlsym("secp256k1_verify");

int result = secp_verify_func(argv[1], strlen(argv[1]),

PUBKEY, strlen(PUBKEY),

hash, 32);

if (result == 1) {

// Verification success, we are returning 0 to indicate contract succeeds

return 0;

} else {

// Verification failure

return -3;

}

}

In this example, we first read all of the transaction content into the VM to obtain a SHA3 hash of the transaction data, and will verify that the public key specified in the contract has signed this data. We provide this SHA3 transaction data hash, the specified public key and the signature provided by the transaction originator to the secp256k1 module to verify the specified public key has signed the proposed transaction data.

If this verification is successful, the transaction originator can use the cell referenced by the current input and the contract is executed successfully. If this verification is not successful, the contract execution and transaction verification fail.

User Defined Token (UDT) Example

This example shows a cell validation script that implements an ERC20-like user defined token. In the interest of simplicity, only the transfer function of UDT is included, though a cell validation script could also implement other UDT functions.

In this example, we first call the system library to read the content of the input and output cells. Then, we load a UDT implementation dynamically and use the transfer method to convert the input.

After conversion, the content in the input and the output cells should completely match. Otherwise, we conclude that the transaction does not meet conditions specified in the validation script and the contract execution will fail.

The preceding example is only used to present the VM functions of the CKB and does not indicate best practices for UDT implementation in the CKB.

Unlock Script Example (in Ruby)

Though the preceding examples have been written in C, the CKB VM is not limited to contracts written in C. For example, we can compile mruby, a Ruby implementation target embedded system to RISC-V binary and provide it as a common system library. In this way, Ruby can be used to write contracts such as the following unlock script:

WebAssembly

In reviewing what we have detailed in this paper, some may ask the question: why does the CKB not use WebAssembly, given the interest it has attracted in the blockchain community?

WebAssembly is a great project and we hope it will be successful. The blockchain and broader software industry would benefit greatly from a sandbox environment that has wide support. Though WebAssembly has the potential to implement most of the features we have discussed, it does not deliver all of the benefits RISC-V can bring to the CKB VM. For example: WebAssembly is implemented using JIT and lacks a reasonable running overhead computing model.

RISC-V design began in 2010, the first version was released in 2011, and hardware began to emerge in 2012. However, WebAssembly emerged much later in 2015, with an MVP released in 2017. While we acknowledge WebAssembly has the potential to become a better VM, RISC-V currently has the advantage over WebAssembly.

We do not completely discard the use of WebAssembly in the CKB VM. Both WebAssembly and RISC-V are underlying VMs which shared similar design and instruction sets. We believe we can provide a binary translator from WebAssembly to RISC-V to ensure that WebAssembly-based blockchain innovation can be leveraged by the CKB.

For languages that only compile to WebAssembly (for example, Forest) we can also support these languages in the CKB.

Summary

With the design of CKB VM, we aim to build a community around CKB that grows and adapts to new technology advancements freely and where manual intervention (such as hard forks) can be minimized. We believe CKB-VM can achieve this vision.

NOTICE: CKB-VM is an open source project like CKB which also respects open standards such as official RISC-V instruction sets. Although most of the CKB-VM design is settled, CKB-VM is still in heavy development and the design can be improved in future. This article is to give our community a taste of CKB-VM so everyone can play with it and contribute!

If you have any questions/feedbacks, we would love to hear from you! Feel free to reach out to us here(Nervos Talk)or via:

Thanks for the input from Jan Xie and Matt Quinn!

🔗👉查看原文,获得更多精彩留言。